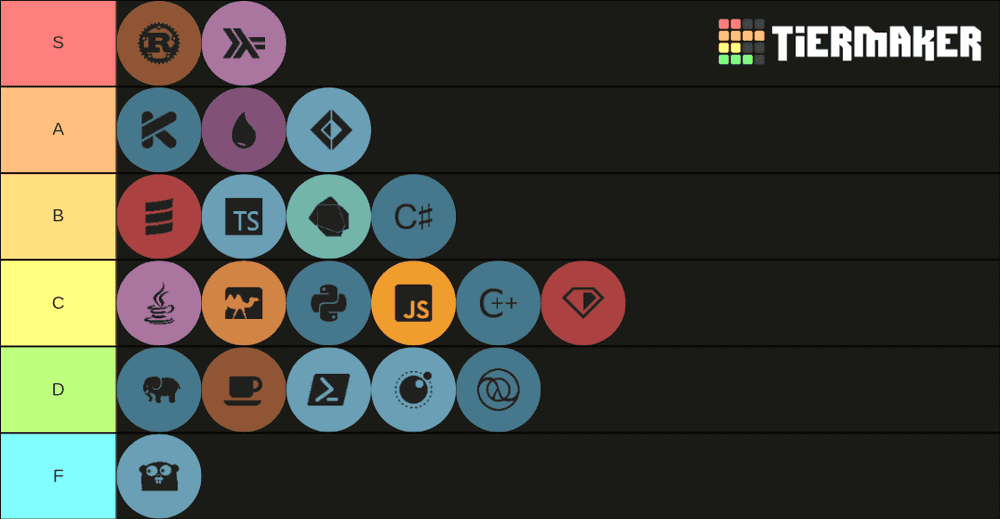

A month or two ago, I put an image of a tierlist of languages that I like using in my Github readme, ranked from F to S tier. F being my least favorite, and S being my favorite. It looked something like this:

- (S) Rust, Haskell

- (A) Kotlin, Elixir, F#

- (B) Scala, Typescript, Dart, C#

- (C) Java, Ocaml, Python, Javascript, C++, Ruby

- (D) PHP, Coffeescript, Powershell, Lua, Clojure

- (F) Go

Part of me obviously just wanted to put that up to get reactions out of people. It’s a little bit nonsensical to try to rank programming languages in a tierlist. I’m not sure what you’d have to be looking for to compare a language like Dart with Powershell.

I had opinions on a few more languages, but the tierlist I was using didn’t have them. Maybe I’ll make my own website for ranking programming languages at some point.

Anyways, plenty of people were upset over how I placed their favorite languages in the C tier. Some people were surprised to see their choice, like Haskell and F# at the top. But Gophers were FURIOUS that their favorite language was the only one at F tier and demanded an explanation from me, pressing a metaphorical knife to my throat.

So let me explain what I have against Go. Also, just as a disclaimer, I don’t like hating on languages too much. Most of them just want to be tools and have their own shortcomings. But a lot of problems Go experiences seem to be self-imposed restrictions through an ideology that wilfully ignores decades of important language research, which just doesn’t make sense to me.

Correctness

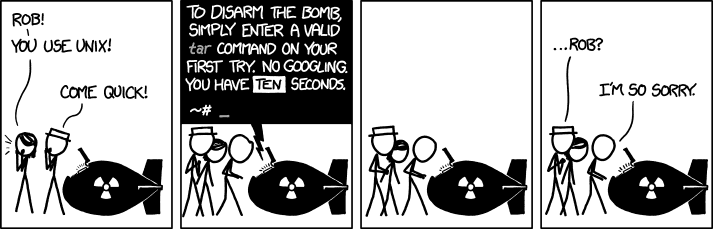

I don’t know about everyone else, but I am a pretty bad programmer. I often make silly mistakes in my code or skip important things in code review that I should be catching. I’m confident in my skills, but if you were to put a gun to my head and tell me my code has to work as intended in my first attempt to save my life, the last memory flashing before my eyes would be something like:

TypeError: cannot read "name" of undefined

I want a compiler to have my back. We humans suck when it comes to keeping complex conditions and details in our heads, but computers are basically designed to be good at that. I want a computer to tell me when I’m making a mistake at the time of writing the code. Hell, I wish the computer could just write the code for me to begin with. At the end of the day, I just don’t want to hope that every single person I’m working with is just a God developer who can catch every mistake before changes are pushed to production because that just doesn’t ever happen.

Golang claims to be a proponent of this concept too, and it shows that by enforcing one of the most annoying linter warnings of all time in the form of an error directly inside the compiler. The one where it prevents your program from compiling if you have an unused variable anywhere in your code.

After all, if you have unused variables, chances are you might have done something wrong. It doesn’t make a whole lot of sense to declare a variable and not use it. This is a perfectly reasonable argument to make.

Unfortunately, if you’re used to commenting things out when developing, this is going to force you to jump through a bunch of hoops and have somewhat of a clown moment in your codebase just to test stuff out.

Aside from being unbelievably annoying, I think workarounds like these arguably become a bigger vector for bugs in your code than leaving things unused or having linter warnings. Once you’ve decided to go down the workaround route, you’ve decided to add a hack into your code to solve this issue, but are still implicitly relying on the compiler to let you know when things are unused. When you make changes later on, and that variable turns from a simple unused variable into a legitimate bug, you feel confident in the correctness of a program that is no longer being enforced by anything in that specific instance.

Overall, I actually think this is an understandable check to have in a language that is truly concerned with correctness. If your language believes it should be as difficult as possible for a developer to add bugs in their programs, making life difficult in ways that feel unnecessary is just one of the Ls that developers have to take for extra safety. Even when that involves the language making controversial decisions or disrupting devs development cycles.

The only problem is, Go doesn’t seem to be interested in safety or correctness at all. It wholeheartedly embraces null pointer exceptions —which tends to be by far the most common source of bugs in languages that implement it— by creating an error handling system where dynamic values can be null at any time with no compiler checks involved. You simply have to remember not to create bugs and to check errors before dealing with error-able values. Quite a different philosophy from the one Go’s unused variable check would like to have you believe it adopts.

Claiming to care about safety through questionable checks and not addressing null pointers is kind of like if a city tried to combat crime by enacting a curfew after 8pm. Certainly a valiant effort that will help maybe… a little bit? But it makes everyone’s lives significantly harder and doesn’t do anything to address the obvious issue at hand.

Go

This is in contrast to a language like Rust, which won’t let you shoot yourself in the foot with any value that may be an error or undefined.

Rust

Not to mention, for the amount of emphasis being put on concurrency, Go also doesn’t address the inherent problems that come with it other than by the design of the language itself (channels as a means of communication between goroutines and such). It has some checks in place to make sure that things like data races are unlikely, but doesn’t actually go out of its way like Rust to make sure they’re not possible. Safety seems to get sidelined in favor of things like easy adoptability. You don’t need your compiler to prevent the programmer from adding bugs if the programmer just doesn’t add them in the first place, right?

The lack of these kinds of features isn’t always a problem for me. Safety and static typing are really important, but not necessarily a dealbreaker for my taste. I like Elixir enough to put it in A tier (whatever that means at this point) which is a dynamically typed language, mind you. And much like Go, Elixir also does not concern itself with preventing the user from adding bugs in their code too much. But the difference is, unlike Go, Elixir embraces the fact that it can’t ensure there will never be problems. It doesn’t pretend to care about correctness to the point of adding ridiculous compiler checks in ways that don’t add any safety. Instead, it has built-in mechanisms to recover from failure as intelligently as possible as a part of the language, and decides to incorporate failure into the way problems are solved in that paradigm.

Of course, caring about safety in a language isn’t just a binary choice of “this language is safe” and “this language isn’t”. It’s just that Go’s priorities when it comes to correctness and safety seem very misguided. Most of its safety features are implemented in the form of radically opinionated language choices that make people upset like intentionally undeterministic map iteration or the lack of support for variance in its type system. Decisions that make a good-faith effort in trying to prevent the user from firing a bullet at their feet with a gun that does a concerningly good job shooting at feet by design.

Simplicity

The reasoning behind this archaic error checking method and the unused variable thing is that Go wants to be as simple as possible. One way to ensure that simplicity is by only allowing a single “Go way” of doing things. Every engineer working on a shared codebase should be able to hit a problem with a Go-shaped hammer and get a predictable Go-shaped solution out of it. If you’re not allowed to handle errors in any way other than always explicitly passing it back to the caller, for example, there’s no debate to be had about how error handling should be done. Except for when there is a debate, of course.

Go’s philosophy seems to hint that complexity only comes in the form of complex abstractions. That if you are not given complex tools like union types, generics, or macros, your programs will necessarily be simpler. And this to me seems like a child’s way of thinking about how complexity arises in programs. Simplicity does not exist on a linear scale of complicated and not complicated languages. It’s a delicate balance across many things in multiple dimensions. Sure, having too many tools and too many ways of doing the same thing is going to cause complexity like it does with a language like C++, but so will having no tools to deal with complex issues. After all, you can’t be expected to chop down a tree with a steak knife. When your go-to abstraction for generalizing solutions is copy paste, that extra effort you had to spend learning and understanding new abstractions is now going to be used to maintain code written with a steak knife; making understanding a solution built with simple ideas much more difficult than it has to be.

You’d much rather have access to more complex concepts to represent more complex problems in those situations, because complexity isn’t inherently bad. Maybe you don’t want to have to understand what the hell a Semigroup is to add 2 lists together, but you also don’t want to have to copy paste this meme

Go

13 times in the same function and then copy paste that function N times for all data types only to solve an otherwise-trivial problem.

net/protoconn_test.goGo

This idea of simplicity-gone-too-far appears in many places. Go makes extensive use of “tuples” when returning 2 or more values from functions, but tuples don’t actually exist in the language. It uses a keyword range to iterate over maps and arrays, but has no concept of an iterable data type. Plenty of features are implemented in the form of very specific compiler magic, and the only explanation for it is that it’s to prevent you from building your own abstractions. If a language is opinionated in not adding complex abstractions, allowing the user to build their own would kind of defeat the whole idea.

Community

Simplicity on its own is not necessarily a bad thing to strive for, even when done well. But the way Go approaches it is a little… well, I’ll just let you decide how you feel about this quote from Rob Pike, one of the creators of the language.

Rob Pike

The key point here is our programmers are Googlers, they’re not researchers.

They’re typically, fairly young, fresh out of school, probably learned Java, maybe learned C or C++, probably learned Python.

They’re not capable of understanding a brilliant language but we want to use them to build good software. So, the language that we give them has to be easy for them to understand and easy to adopt.

Go doesn’t only want to make your life easier by preventing arguments about menial things. Its philosophy is based on the idea that you’re incapable of dealing with the tools you think you should have. Why don’t we have generics in the language? Because generics are hard and you just graduated from college last year. Copy and paste it instead.

Maybe I’m just being weird here but I don’t really want to use a language built by people who think they’re better than me…? Like, don’t get me wrong, almost everyone working on Go certainly is. I just don’t think this is a healthy way of building a relationship with a community, though this might also be the brash nature of Rob Pike in specific.

This seems to be an issue that shows up in the Go community fairly often. If you look at discussions of problems and proposals like proposal: leave if err != nil alone? #32825, they tend to have a predictable format across the board. In one corner we usually have the “please sir I just want to use a good language” team, asking for changes that they feel are going to make their lives easier. And in the other corner, we have the “you just don’t understand the language man” team, trying to convince the users that they don’t actually want the things that they want; alienating the userbase with a mix of patronization or stockholm-syndrome depending on where it’s coming from.

It seems like this divide exists because Go was never built for a community in the first place; it was built for Googlers. It only ended up taking off with the rest of the programming community due to being open source and its amazing approach to concurrency, which was the main problem they were trying to solve at the time. But because it was never built for a community, it has all of this baggage that makes sense in the context of a company imposing restrictions on its employees with what they believe to be the correct approach, but not with a language open for everyone to use.

It took the language maintainers a ton of pushback from the community on their puritanical ideals about what they think the perfect language should be like to create a language that the people actually enjoy using. Sadly, they’ve tucked all of that away in the promise of a Go 2 that’s still yet to come.

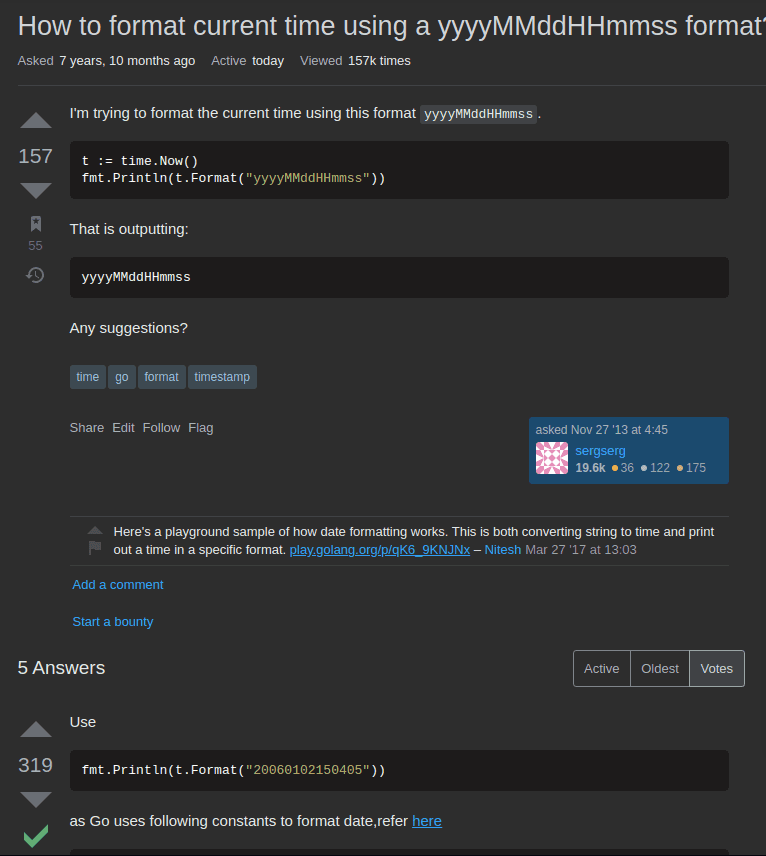

There are some honorable mentions that I didn’t include here like Go’s hilariously bad approach to date formatting.

and a couple others, but I didn’t think they deserve the same criticism because they’re just weird corners of the language and don’t make as much of an impact on the overall experience.

Overall, Go is not built by inexperienced people or anything, or even a bad language depending on what you value. It makes a lot of opinionated choices and deliberate compromises of important ideas to solve problems that I just don’t consider to be worthwhile at all and sometimes even harmful. Go has not learned anything from decades of programming language research and re-implements all the same problems that language designers have expressed endless regret over. The concurrency is awesome, but the pain of actually using the rest of the language simply isn’t worth it.

Just use Rust instead.